April 13, 2020, by Lisa Chin

Are we seriously missing the POINT?

This post is contributed by Dr Csaba Zoltan Szabo, School of Education, University of Nottingham Malaysia (UNM)

Recent exigencies faced by educators because of Covid-19 have inundated the media with positive vibes around ‘much needed innovations’, ‘novel digital solutions’, and ‘the future of education’. However, as educators we ought to think seriously and, indeed, adopt a critically evaluative stance on this imposed digital home-learning conundrum.

Scientists of Education and related fields (Psychology, Applied Linguistics etc.) have always had a vested interest in exploring what makes teaching and learning effective and how we can ameliorate traditionalised teaching practices. Fortunately, in many classrooms, traditional didactic strategies such as choral repetition, the audiolingual or grammar-translation language (and science equivalents of these) teaching methods are long gone, although, the occasional two-hour teacher-centred lecture is still common. Empirical evidence from meta-studies on effective teaching shows that a number of factors have a high impact on learning, but whether these can be effortlessly transferred to an online platform is far from being unequivocally answerable. Leaders in educational settings, in my humble view, are seriously misguided by the notion that literally, from one day to another, teaching across different disciplines can be fruitfully adapted to a digital platform. Still further, insofar as it will benefit students or facilitate learning in a meaningful way. To explain, in this reflective blogpost, I will consider some evidence-based aspects of face-to-face teaching (not traditional by any means) and the challenges I have had in transferring these to an online platform (MS Teams) for a five-hour workshop on Doing Statistics in R.

-

Learning is understanding, not remembering

In a hands-on session in which participants from various backgrounds learn about using a specific data analysis software, making sense of the underlying logic behind a command or the sequence of certain steps is absolutely key. While a face-to-face session enables the lecturer to pause after an explanation and check for understanding, this felt less effective in the online session. At regular intervals, I did stop to ask students whether the information was clear or if they had any questions. Only 5-8 students actually used the chatbox to say “yes” or “all clear”. Not being able to see students’ (confused) faces made it hard to acknowledge what the other 30 students understood from the previous explanation.

TIP: this can be partially overcome by using the Polly app in MS Teams and asking students a follow up question (the speed of answers might be revealing about the extent to which students are with you in that session and might encourage them to engage more).

-

Mastery what?

A key strategy of effective teaching is mastery focus. This, in brief, entails the teacher taking on the role of a facilitator to ensure that a large majority of the learners master the specific subskill, understand the concept, or successfully complete the task or activity. In a traditional session, I could simply walk around the room and check students’ laptop screens to gauge whether they had drawn the graphs correctly or used the right variables for a statistical test. The benefit of this was that, in a short amount of time, I could probably support 15 students relatively quickly by pointing out where they could improve or how to problem solve.

During the online session, I felt completely in the dark. I was aware that at least a few followed along because they actively used the chatbox, but since I could not see their screens, I had no reliable means of telling whether they had indeed succeeded in the task or not. Furthermore, problem-solving took what felt an enormous amount of time as (1) participants had to explain what they did, (2) I had to understand what could have gone wrong, and then (3) I had to find concise answers to support them in rectifying mistakes. While in a face-to-face session this happens on a one-to-one basis, in this instance we had around 40 students listening to our communication barriers imposed by the virtual network. Consequently, mastery focus can be relatively easily implemented in a traditional classroom environment, but is hard to replicate online. This links well with the following points.

-

Collaboration, cooperation, and assistance

This particular face-to-face session, due to its complexity, has always been set up in a way that students can collaborate on tasks and they have plenty of assistance. To be proactive about this, I asked senior students and graduate students in need of teaching experience to join the session to provide support to the students. This worked extremely well because those who made the occasional errors or got lost due to technical difficulties could raise their hands and assistants could help them solve the problem and catch up. This ensured inclusion (and mastery focus) for a very diverse group of students. Similarly, some students are very good with technology, while others have the statistical understanding. As a result, the face-to-face sessions could be characterised as a dynamic, active learning environment where students complement each other in terms of skills and knowledge, and collaborate in order to reach specific learning objectives.

Although I did ask a graduate assistant to provide support (THANK YOU again Jun Ho Chai, PhD candidate from Psychology) and we set up a Questions and Assistance channel in Teams to attempt to replicate this supportive environment, the result was nowhere near as effective in the online session despite our best efforts. As it transpired, the specific Q&A channel was only used by some students, albeit that questions did get frequently posed in the general chatbox. My overall impression is that the lecturer being almost completely in the dark, not being able to ensure mastery focus and the lack of a collaborative environment, further exacerbates the achievement gaps between high and low-performing students – something that perhaps lecturers across all disciplines can reflect on.

TIP: If online sessions are part of a sequence and there are fewer time constraints (unlike this session), both mastery focus and collaboration can be (again) partially overcome. For example, by assigning students into mixed ability groups for reciprocal teaching and giving them a task to complete through collaboration. They can then upload the results to their specific Teams channel. Albeit this is still less effective than face-to-face interaction in my opinion, but at least working online in smaller groups allows students to collaborate and digitally socialise (increasingly important in this physical lockdown period).

-

Multidirectional feedback and constructively aligned assessments

Feedback is one of the most impactful strategies for student learning and well-developed assessments that align with the learning objectives also aid learning and long-term retention. When it was held in a physical classroom, feedback in this workshop was multidirectional in the sense that I, as a facilitator, could easily get feedback from students by asking questions, checking work, or simply catching confused facial expressions. Students could also get feedback from the assistants and me through our indications of where they needed to improve or simply congratulating them for getting it right. Importantly, a large volume of feedback was peer-to-peer. Students could check each other’s error messages or, through collaboration, reinforce their own thinking or solutions. Both formal and informal assessments in a physical classroom would further facilitate learning. The session is planned in a way such that at regular intervals students receive small tasks to complete on their own, which, in turn, prompt feedback in an interactive session and facilitate achievement of the intended learning outcomes.

Conversely, in the online session, multidirectional feedback is virtually (excuse the pun) impossible. The feedback I received from students on their successes was very minimal, which deprived me of the opportunity to praise, celebrate success, show enthusiasm or motivate further. Likewise, despite the regular breaks and pauses in order to avoid cognitive overload, the formative and informal assessments I regularly employ in the session were less effective, if not completely ineffective.

-

Engagement and knowledge construction

It emerges from the above points that a solely online learning environment has an impact on both teachers and students. The lack of collaboration potentially reduces the level of engagement for less motivated students even further. The sense of competitiveness in finishing tasks first might be reproducible in an online environment, however, it may also be hindered by external factors such as the speed of the internet or device. Discussions amongst students and the lecturer add considerably to knowledge construction and the reinforcement and retention of new concepts. However, the expectation that students and educators shift all their education-related interaction to various platforms smoothly is unrealistic at best. The extent to which we are culturally, socially, and communicatively handicapped in a dark digital classroom, especially until new behaviours are formed, should be evaluated in our individual pedagogical contexts. It appears that evaluating the extent to which students engage in our online sessions should become part and parcel of teaching if it hasn’t been thus far.

-

The teacher, the humour, and other social aspects of learning

Besides the above evidence-informed strategies for effective teaching, we must not forget that one of the most important factors in learning is the teacher – their personality, attitude, enthusiasm for the subject and students, and their ability to build rapport with students. Surely, we all remember the funniest teacher or the one we feared most as students, even if the content they taught has faded into oblivion over the years. A sense of humour, and indeed the occasional sarcasm, is part of many teachers’ identities and, in many cases – besides their pedagogical and content knowledge – it is what makes them highly effective and popular. Yet in a virtual space, we are forced, by suppression of our personalities and educational creativity, to fit into the template of the educational platforms and comply with these. During the aforementioned online workshop it seemed incredibly difficult to use either humour or sarcasm due to the lack of physical presence of my students. Does online teaching fail to capture elements that make us successful teachers? Or is this something that develops in us over time and with experience on digital teaching platforms? While we reflect on these questions, it is perhaps imperative that we remain cognisant of the impact of changes and re-evaluate what success means in our own individual practices.

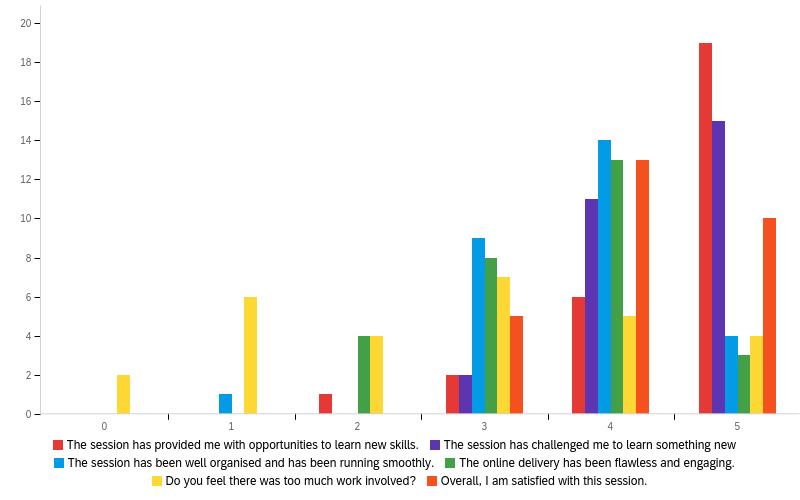

Overall, our comprehensive post-session feedback survey that builds on the usual SET/SEM questions indicates that out of 28 respondents, 23 either agreed or strongly agreed that they were satisfied with the session while 5 stayed neutral. The tables below give some further reassurances regarding the success of the session.

Table 1. Evaluation of the online session in R

Please rate: 1 = strongly disagree, 2 = disagree, 3 = neutral, 4 = agree, 5 = strongly agree

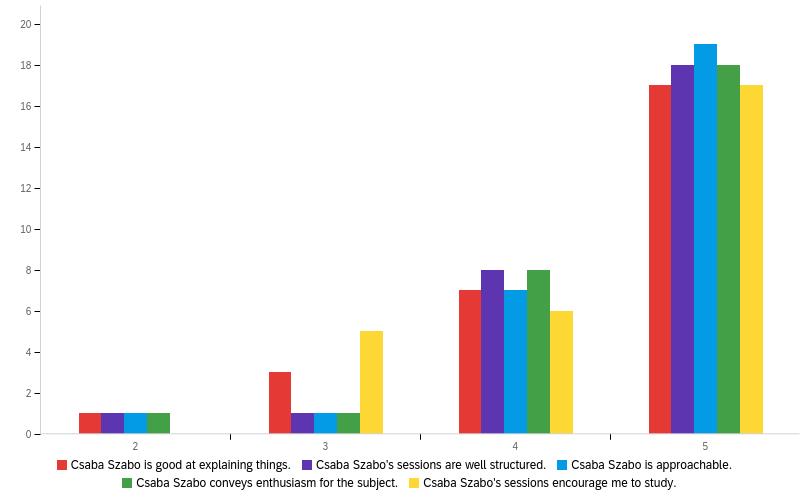

Table 2. Evaluation of the trainer

There is also a bigger picture. The training of educators and English language teachers happens beyond the classroom as well as in it. English language teacher trainees in our international university benefit enormously from the opportunity to socialise and practise their English skills and communicative competence both in formal and informal settings. This, however much we embrace and innovate technology, is hard to replicate from home even through digital classrooms. Therefore, students must not be treated as de-personalised data points where they sign into a session and that is taken for attendance, let alone learning. Online platforms can be characterised, if content is not carefully transferred into the digital space, by the comorbidity of such conditions, admittedly and purportedly, at their current stage.

So, are we missing the POINT (Power Of Internet, Necessity, & Technology)? It is unquestionable that the internet is a very powerful tool. It certainly enables us to continue the large bulk of our teaching and assessment efforts, which is reassuring for employers but only for some students. The various technological innovations and our burgeoning interest in them provides the often creative means to transfer our teaching online and engage students remotely. Nevertheless, we should not forget that all of this is out of necessity and (hopefully) is not the beginning of wholly online future for the delivery of Higher Education programmes. It remains the case that the effectiveness of these efforts both depends on the individual teacher, the specific subject, and of course, the institutional support that universities provide academics in terms of training and, very importantly, time. Certainly educators’ and the platforms’ ability to teach online will greatly improve over time, especially with the wider use of AI and virtual realities. Until then, it is crucial that we carefully monitor and re-evaluate our successes. We also need to celebrate the meaningful adaptation of educators in these challenging times and acknowledge that technology is indeed indispensable to effective teaching. However, it cannot be the sole delivery system for holistic education in entire programmes. Not yet, anyway.

Commercial and educational intuitions in the online teaching business spend considerable amounts of time and resources on creating online materials, often with a team of experts in the content, technology, and digital education. The expectation from educators that suddenly they possess all the requisite skills and knowledge in creating effective digital learning opportunities for their learners studying at home, often effectively from one week to the other, is borderline delusional. The emphasis here is on effectiveness. What about lecturers who fail to engage students in the learning process or build a good rapport with them even in physical settings? Is it legitimate to expect them to be successful at this in digital modalities, which in often lacking the personal touch merely exacerbate the problem? Although teachers and university professors are remarkably adaptive, it is hard to state with any degree of certainty that these efforts are either effective or meet the expectations (learning objectives) of a diverse student population in a fair system that is built on equality and inclusion.

MOOCS reach millions of individuals across the world, but providers after spending large sums, often from the public purse, report massive dropout and low completion rates. Furthermore, many students do not access over half of the materials or participate in forums or additional (and essential) aspects of the course that would make it more effective. Surely, there must be a reason for this, which makes any aspiration to move complete degree programmes fully online in a short amount of time while maintaining effective holistic teaching appear wrongheaded. In other words, if even well-funded and expertly designed and rigorously reviewed MOOCS (including cMOOCS, xMOOCS, or hybrid/blended MOOCs – do google these if interested in their characteristics) face such challenges, how certain can we be that our efforts will lead to success?

At the risk of stating the obvious, for educators to transfer their teaching online, uncritically, without considering the nature and goals of education beyond delivering the core content, appears flawed and opportunistic, at best. In current times of necessity, digital education can provide certain solutions but a business-as-usual attitude towards teaching is risky, unsubstantiated by evidence, and purely unscientific, as it disregards the cultural, social, psychological impact on learners and disregards the time that enables all educational stakeholders to adapt.

It is nonetheless not the case that we should not embrace the affordances provided by digital teaching platforms, especially under the current circumstances. Through trial and error, we can explore ways to capitalise on evidence-informed teaching strategies and how these can be combined with technology to suit our students’ needs. However, allowing empirical evidence to catch up with effective digital home education and its affordances is imperative. Until then, let’s hope that enforced digital home teaching becomes a never-reoccurring nightmare that we can soon all forget.

What do you think of these issues? Do you consider teaching online as an optimal medium for knowledge transfer? Share your views! The School of Education UNM plans to launch a weekly blog that gives an open platform for educators across ALL schools. Email your success stories or critical reflections to csaba.szabo@nottingham.edu.my.

-

Post a comment